- Home

- Gulwali Passarlay

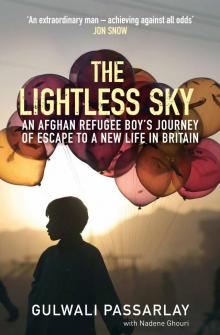

The Lightless Sky Page 7

The Lightless Sky Read online

Page 7

I couldn’t help myself. ‘No, please, don’t. We’ll think about it, OK?’

‘Think about it? You think you have a choice?’ The man snorted with derision. ‘You really are wasting my time now. I am not an unkind man, but this is my home, and my rules. You are going to need fake papers – but that won’t happen until you get closer to Turkey. Until then, you are safer not having any papers at all.’

Mehran shook his head. ‘Look, these are our passports.’

‘“Our” passports? Weren’t they provided by Qubat? These are his property, not yours. They served their purpose to get you here, but you don’t need them now. Give them to me.’

‘No.’

We were clearly getting nowhere. I didn’t want to hand over my passport either, but nor did I want to stay in that stinking guest house a moment longer. ‘I don’t think he’s lying. If it’s for our safety, we should.’

A couple of hours later and four brand-new Afghan passports were in an envelope on the reception desk, weighted down by an illegal bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label.

We all hated the man and his smelly guest house. Everyone was really worried about what had happened, and Mehran wasn’t speaking to me because he said it was my fault that we had given in.

But, as good as his word, the man dropped us at the coach station and gave us tickets for the bus to Tabriz.

It was another overnight journey, but this time I was too scared to get any sleep. When we finally arrived, it was into a much smaller bus station, and it was a relief not to be hassled by taxi touts on arrival.

A heavy-set Iranian Kurd approached us. ‘Qubat?’

By now we knew the ropes. ‘Yes.’

He issued instructions to the others in a mixture of Farsi and a language I had never heard before, which I assumed to be Kurdish.

‘It’s time to go. We still have a long drive.’ He looked down at me and my little backpack. ‘Is that everything you have?’

I nodded.

‘So then…yallah – let’s be going.’

I have no idea how, but six of us and our bags managed to squeeze into his Toyota. We rattled out of Tabriz and into the Iranian hinterland.

After an hour or so, the Toyota started to work harder as we curled up arid foothills. Our driver hummed along to loud pop music; he hadn’t spoken a word to us since we’d set off. My legs had long since gone numb.

The road eventually straightened and I could see that, up ahead, it seemed to go right through the centre of a large lake. Big black rocks covered in wire formed a barrier on either side of the road, and the traffic had begun to form a large queue.

I started to feel a sense of rising panic. Was this a border?

‘What’s happening?’ I whispered to Abdul, who was sitting to my left.

He shrugged. He very rarely spoke.

The Kurd suddenly pulled over to the side of the road, got out and opened the nearest passenger door. ‘Yallah. Get out. Let’s move it.’

On foot, we followed him, making our way alongside the traffic. Up ahead I could see that the lake widened and stretched out into the horizon. The queues of cars were easing on to a large ferry.

The Kurd had gone over to some machines and now came back with a handful of tickets. He spoke in Farsi. ‘Act normally. Try and behave like tourists. Enjoy the view.’ He pointed to a gangplank where a handful of foot passengers were boarding. When I next turned around, he’d disappeared.

This was my first time on board a boat. And even though Afghanistan has lots of lakes, I had never seen one this big or wide. To me it looked as I imagined the ocean would – something else I had never seen.

Most passengers stayed in their cars. There were no seats for foot passengers, and my legs swayed beneath me once we had found a place to stand, by the edge of the boat. The water was flat and placid but, as I looked over the edge into the deep, blue water I found myself having another attack of acute homesickness, and I wished I had someone to hold my hand and comfort me. But I didn’t want the others to think I was a baby so I tried to act brave and nonchalant, as if I did this sort of thing every day.

The crossing took about fifteen minutes. As we approached the shoreline on the opposite side, the driver mysteriously reappeared by our side and hissed to us to board a green minibus that was sitting in the centre of the ferry. Behind its steering wheel sat a different man.

We got in and, as the ferry came to a standstill, our new chauffeur drove off. About an hour later, in the middle of some quiet countryside, he pulled over behind a blue off-road vehicle.

‘Please change cars.’

They were the first and only words he spoke to us the whole time we were with him.

A third man drove us on. The road was good and as we travelled down an empty, winding road, the terrain began to change: trees dressed in October’s autumn hues of gold and burnt orange lined our way. I was taking the first driver at his word and trying my best to enjoy the view.

‘We should be there soon.’

It was nice of the driver to reassure us, except he failed to mention where ‘there’ was. Mehran asked him where we were going but no reply was forthcoming. At some point, the driver took a call on his mobile phone. He spoke in short, hurried bursts of Farsi mixed with Kurdish, and so quickly that I could barely understand even the Farsi words. But I did notice that after the call his mood changed, and he became sweaty and nervous.

As a car approached on the other side of the road, he flashed it to stop and wound down his window. He spoke in Farsi to the other driver, so this time I could work out the gist of it: ‘Are they checking cars ahead?’

‘No, I just drove straight through.’

A few minutes later we cruised through an unguarded police checkpoint.

‘Allah was on our side today. They usually check the vehicles here.’ His relief was short-lived, however. Fifteen minutes later, as we wound uphill into a village, the engine cut dead.

‘Shit. This isn’t good.’

We could see what he meant: there was a police station to the right, just a few hundred yards ahead.

‘Stay inside and try and keep your heads low.’ He got out and lifted up the bonnet, fiddling around inside, then he came around to the driver’s window. ‘It should be OK, but we need to jump-start it. All of you get out and push. Let’s just be fast and get out of here.’

We managed to get moving again just as two policemen ambled down the road towards us. Thankfully, they barely paid attention as the engine barked into life and we piled into the car.

It was late afternoon when, a few miles later, we turned into a cluster of low, concrete-block and traditional stone buildings, surrounded by fruit trees and high fencing.

Dozens of cars were lined nose-to-tail in front of a dilapidated cow shed. An imposing-looking man stood in the yard waiting for us.

‘I am Black Wolf,’ he said, shaking our hands as we got out of the vehicle.

His eyes were as dark as the colour of his name, but they seemed kinder than the name suggested. He shook down a large gold watch from beneath the sleeve of his white tunic, making a show of checking the time.

‘Welcome to my house.’ He gesticulated with a sweeping arm. ‘I apologize for your inconvenience with the different vehicles. But you are here now.’ He smiled, showing near-perfect white teeth. ‘Welcome to our Kurdish heartland. I will show you where to sleep, and bring you some water.’

He spoke beautifully articulated, crystal-clear Farsi, even though he, like the driver, was obviously Kurdish.

‘Ignore these men,’ he continued, waving his arm at three men busily syphoning fuel from various vehicles’ petrol tanks into battered orange fuel drums. ‘They will not bother you, and it is none of your business, anyway.’

Whatever Black Wolf was up to, I got the impression business was good.

‘Com

e, gentleman,’ he said. ‘Follow me.’

We followed him past a pile of car parts and scrap metal, between two further stone buildings and towards a large, very modern looking house, entering beneath a smart looking porch.

As Black Wolf gesticulated to a door just to our right, I noticed a large diamond and emerald ring glinting on his finger. ‘Here,’ he said. ‘This is your room.’

It was well furnished, with traditional mattresses around the sides and Iranian carpets on the floor.

‘You can help yourselves to fruit any time,’ he said, pointing towards a large orchard. ‘But be quiet, and discreet.’

Through the net curtains of the window I could see trees heavy with apples, oranges and pears – the likes of which I hadn’t eaten since I had left home. My stomach went into a frenzy of rumbling.

‘There is a tap on the side of the building and a toilet around the side.’ Black Wolf smiled and ruffled my hair. ‘Don’t look so worried, boy. No one is going to hurt you. You are going to rest here for a few days until I get word it’s time to move on.’ He looked up at the rest of the group. ‘The next part of the journey is hard. You will need strong legs, so I expect you all to behave with good manners and sleep as much as you can. If you see that I have other guests, please stay in your room. You definitely do not want to make any trouble for me.’

With that he turned on his heel, speaking over his shoulder. ‘Someone will bring you some food shortly. I suggest you make yourselves comfortable.’

Too exhausted to talk, we flopped down on to the mattresses.

I was shaken awake.

‘Hey, Gulwali.’ It was Mehran. ‘Wake up, man. It’s food time.’

I was confused by the half-light.

‘It’s almost dark. You’ve been snoring for hours.’

A lanky, teenage boy was in the room. He placed a large dish of rice, a steaming roast chicken, a pot of lentil stew and a traditional Kurdish salad of olives, cheese, cucumber, tomatoes, lemon and cabbage on a cloth in the centre of the room. It was a feast.

Black Wolf strode in carrying a pile of plates. ‘This is Rizgar, my brother’s son.’ He nodded at the boy. ‘Come on, then. Take a plate – get eating.’

He smiled in my direction. ‘Don’t delay, little boy. Get eating before the fat one beats you to it.’

Shah glowered at him as we all laughed.

As six hungry people sat eating cross-legged in silence, I found myself staring out of the window into a star-filled sky. The stars shone almost as brightly as they did in the mountains of my childhood.

It had been just over a week since I had been ripped away from my family and everything I had known, but the pain of each hour had made it feel like months. After the meal, when we said our late evening prayers, I asked Allah to keep my family safe.

I woke very early the next morning. It was still dark. The others were fast asleep, so I stepped around them quietly and went out to visit a beautiful horse I had spotted in a field next to the orchard the previous evening.

I took a pink apple from a tree and held it over the fence. There was a large shadow in the distance. I clicked my tongue against the roof of my mouth and the shadow moved closer.

The mare was a beautiful chestnut with a shiny coat that glowed even in the pale light. Her muzzle twitched as she scented my offering, and large white teeth crunched up the apple in two easy bites.

It felt peaceful being alone with this graceful animal, and I couldn’t help but be reminded yet again of my early years living with my grandparents in the mountains. How could I have had any idea then of the pain and suffering that was to come to me and my family?

The strains of the dawn call to prayer floated across the trees from a distant mosque as a softly pink light began to melt the clouds. I hurried back through the orchard back towards the main house.

‘Little boy.’

The voice felt loud in the still morning air.

‘Hey, little boy.’

Black Wolf loomed over a low wall that marked the entrance to the back of the house. ‘Are you coming to pray?’

‘Where?’ I really wasn’t sure about this.

‘Come, boy. Come inside.’ He waved a hand, his jewelled ring glinting in the dawn, beckoning me towards him.

I did as I was told, stepping through the back door into the inner sanctum of the family quarters. A group of figures stood in the middle of the central courtyard, faces towards Mecca.

‘Little boy, this is my brother and my cousin. My nephew you already know.’ He nodded to me, and then addressed everyone. ‘Let’s pray, brothers.’

I joined them as they fell on their knees. I thanked Allah for a merciful journey and prayed for his blessing on my mother. I asked him to keep my brother safe until we were together again. And I thanked him that Black Wolf was a kind man.

When we finished I felt much better – very calm and comforted.

Black Wolf looked over at me. ‘Will you take some breakfast with us?’

I beamed. ‘Thank you.’ It was a great act of generosity by Black Wolf to allow a male who wasn’t a direct relative to meet his family. I was nervous. This was the first time I’d been in the company of Kurdish people.

I knew from geography classes at school that the Kurds are the largest ethnicity in the world without a country of their own. They historically inhabit the border regions of Iran, Turkey, Syria and Iraq, but they don’t recognize the boundaries between these countries. Like the Pashtuns, they also have a very strong sense of identity.

Perhaps I should have been more careful, but Black Wolf had a relaxed manner and an easy charm, and I was fascinated by him. The way he moved had a confidence about it – as if he knew with absolute certainty he was the lord of all he surveyed. He reminded me of the tenth-century merchants I had read about in history books – the men who made this region famous for its rich trade routes.

If I still had any misgivings, they evaporated the moment his wife and her sisters-in-law caught sight of me.

For a moment I was taken aback at his wife’s beauty: she wore a loose scarf around her neck, allowing her long black hair to escape on to her shoulders, but then the little boy who had taken family honour so to heart back at home became outraged – I wanted to tell her to cover her hair more carefully.

But my childish moralizing flew right out the window as his wife gushed: ‘Oh, isn’t he adorable? How cute.’ As she spoke, she tousled my hair in a way that was intended to both embarrass and delight me in equal measure.

The women’s teasing continued even as the men sat to eat first – the women would eat once we had finished. We ate flat bread, rich with olive oil, dunked in smoky baba ghanoush and some of the dhal I recognised from the previous evening’s meal. We finished with delicate glasses of sweet, black tea.

Black Wolf sat back and lit a cigarette, picking a fleck of breakfast from his teeth. Tendrils of smoke oozed from his nostrils. ‘So,’ he said, cocking an eyebrow at me. ‘Are you recovered from your journey so far?’

‘Yes, thank you.’ Then, to my horror, I suddenly felt tears spring to my eyes – perhaps because his family reminded me so much of my own. I chastised myself for being so silly and tried to hold them back, but it was too late. Black Wolf had seen them.

‘I wish I could say I hadn’t seen many children like you on this path, but I have. Too, too many. It’s a sad world.’

My tears flowed unchecked now, and when his wife dabbed at my eyes with a tissue, the act of maternal kindness was just too much. I grabbed the tissue from her and looked at the floor as I struggled to find the right words in Farsi to make myself understood: ‘My mother sent us away. I don’t know where my brother is.’ At that, a series of big, gulping sobs escaped me.

Black Wolf and his wife looked at each other and shook their heads sadly.

‘This is unfortunate. But I am su

re you will find him again. You have a long way to go and will no doubt cross paths with many unscrupulous men. Take my advice, little boy – do not trust these people, these so-called people-smugglers.’

‘But aren’t you a people-smuggler?’ I blurted out, immediately regretting the way it sounded.

Black Wolf bristled for a moment, taking another pull on his cigarette. ‘Me? You do me an injustice, boy – and under my own roof, too.’

His family laughed at my obvious discomfort.

He waved a hand for dramatic affect. ‘I am a mere facilitator. My business interests lie in other directions.’

His brother, cousin and nephew laughed again.

‘No, I am merely a man who has a well-located farm where people like you can stay until the smugglers are ready to move you on. I provide a service, and offer a level of discretion these men find comforting.’ With that, he sent another cloud of smoke billowing up to the yellowed ceiling. ‘More tea?’

When I rejoined my friends, I wasn’t their favourite person.

‘Gulwali, you idiot, where the hell have you been? You missed prayers.’ Mehran did not look happy.

Even Baryalai raised his voice. ‘I told you to stay with the group. Do you think we need the drama of worrying about you as well as ourselves?’

I tried to joke my way out of the situation. ‘What? Did you guys eat breakfast without waiting for me?’

Even Abdul said a rare word: ‘Gulwali, you haven’t answered their questions.’

I was about to tell them, but then something stopped me. I had a sense that, however nice they were, they’d resent the fact that I’d just been given special treatment.

‘I was seeing the horse.’

‘A horse? In the dark? Do you want to get arrested?’

I felt a bit ashamed. ‘I did pray. I prayed outside.’

They refused to speak to me all day.

For the next four days we settled into a fairly relaxed routine of eating, sleeping, praying and playing cards. Or rather, the others played cards – no one offered to teach me, and I felt too embarrassed to ask.

There were a couple of Kurdish story books on a shelf in the room. Like Pashtu, Dari and Farsi, the Kurdish language originates from Arabic; and, like most Afghan kids, I’d been taught to read the Quran in Arabic from a very young age. So I reckoned if I tried, I might be able to make out a few words.

The Lightless Sky

The Lightless Sky